- Home

- Miguel Flores

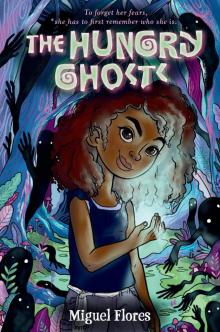

The Hungry Ghosts Page 7

The Hungry Ghosts Read online

Page 7

“Made what easier?” She climbed up next to Jasper and looked in the direction he’d been staring. She gasped.

There, in the middle of the bamboo forest, was a large, magnificent tree with a trunk as wide as a house. In fact, maybe it was a house. A knot of wood that could have been a doorknob protruded from the base, and several openings that could have been windows were carved into its bark.

That, however, was not what had caught the attention of our two friends.

Circling around the top of the tree were dozens and dozens of flying broombranches. They shook their yellow straw leaves as they whistled by, rustling and making their own sort of percussive music. They flew around and under and between one another, diving in the air and looping around the tree’s larger branches.

For a moment, Milly wondered why the tree’s shape looked so familiar. Then she realized: it looked just like Elma! Is this what Elma had been like before the war? A broombranch tree?

Milly shifted her weight and something snapped underfoot.

The broombranches all instantly darted out of the sky and into the tree’s canopy. Their knotted ends twisted perfectly into the tree’s branches and they preened their leaves until they looked like a normal tree from a distance. In a fraction of a second, the entire scene had gone silent. The only sound came from the faint teasing of the winds above, wondering why their broombranch friends had stopped dancing with them.

Milly remained frozen. She glanced down at the cat and whispered, “You don’t think the witch lives here, do you?”

The cat sniffed. “I don’t know. This tree should practically reek of magicks, but I don’t detect anything. It smells like nothing, like it’s not even there.”

“This is very strange,” Milly said. “I don’t like it.”

“Me neither.” The cat wiggled his haunches, then jumped down. “Oh well!”

CHAPTER EIGHT, PART TWO

a world without boundaries

“Jasper,” Milly hissed. “What are you doing?”

“I’m gonna ask a broombranch for a ride,” he answered matter-of-factly.

“Jasper, stop.” Milly scrambled after him. “I don’t want to ride a broombranch. I don’t even know how to fly!”

“You’re a witch, aren’t you? If there’s anything I’ve heard you humans say about witches, it’s that they serve their cat masters and only travel by broombranch.”

“That’s not true. What would you know about witches?”

“They’re all you humans ever talk about. Every year I wait for prayers to drop from that cliff of yours and all I hear are things like ‘Please don’t let the witches come back’ or ‘Keep me safe from the witch in the woods’ or ‘Bless the wizards for banning all the witches forever and ever, amen.’ You’re a very fearful lot, you know. Actually, your prayer in particular was very interesting. It wasn’t very big, but it sure was the heaviest one I’ve ever caught. There was something rooted in there, something even heavier than fear. It was almost—”

Milly cut him off. “Okay, okay. Let’s get a broombranch.” She didn’t want to know whatever it was that’d made her prayer so heavy. Milly squinted. “What was your plan gonna be?”

“Ask one politely?”

Milly rolled her eyes.

“What?”

“I don’t think they talk.”

“You didn’t think a cat could talk either.”

“But you’re not a real cat.”

The cat shrugged. “Never know until you try.”

“Doubtful.” Milly looked around the small clearing for something with which to get one of the branches. Something at the edge of her vision skirted around the tree.

“What was that?” she whispered.

“What was what?”

She put her finger to her lips and made a shh sound, then tiptoed toward the tree.

The cat followed behind. “What are we doing?” he whispered a little too loudly.

“Quiet, please. I thought I saw something.”

The two crept around the tree and saw a single broombranch peek out. When they spotted it, it ducked back out of sight.

“Did you see that?” Milly said.

“Sure did.”

“Maybe we can—”

“Talk to it,” Jasper said. “Catch it,” Milly said at the same time.

“Wait, what?” They both paused.

Jasper twitched his nose. “Catch it? A broombranch? You’re going to use magicks on this too? Tame another living creature with your special powers?”

Milly felt her cheeks burn. “No . . .”

“What are you going to use? Your bare hands?”

“I mean . . .” Milly scratched her palm nervously. “I use my hands for everything.”

“I really don’t think that’s a good idea.”

“Yours doesn’t sound much better. What if we scare it away? I think we should try to catch it off guard.”

“Fine.” Jasper snorted. “We’ll do it your way. Just don’t be offended when I say I told you so.”

“I won’t have to. I’ll be the one saying I told you so.”

“If you’re wrong, I demand . . . hmm, what is it that cats eat again?”

“Mice?”

“Ew, no. Not that. I demand a cake.”

“Can you even eat cake?”

“Beats me. But I hear enough prayers about it that I’m dying to find out.”

“Okay, if I’m right, you have to stop calling me little person.”

“Ooh, that’s tough. This means I’ll have to remember your name.”

“Exactly.”

The cat twisted his nose. “I suppose that’s fair.”

All the while they’d been arguing, the broombranch had floated closer and was watching them with either apprehension or, more likely, curiosity. In fact, it was near enough that either one of them could have reached out and touched it if they had noticed.*

It wasn’t until a moment later, in the middle of a sentence, that Milly finally noticed the branch and froze.

“Hi there,” Jasper said.

The branch immediately shuddered and tried to fly away. “Grab it!” Milly shouted, and jumped toward it. Her fingers brushed its tail end as it fluttered out of reach and she landed in the mossy grass.

“With what?” Jasper scoffed. “My mouth? I think I’ll leave this to you.”

“Thanks a lot.” Milly scrambled up and held both her hands out in a placating matter. “All right, come on over.”

The broombranch quivered, taunted her, and shifted from side to side.

“It’s teasing you!” Jasper made his awful laughing noise. “How delightful!”

“I can see that!” Milly said through her teeth. She lunged forward again and the broombranch hovered sideways, just barely out of reach.

It rustled its brittle leaves happily.

“It’s too fast!” Milly said.

“Oops. I wonder what other options we could have possibly had.”

“If you’re not gonna say something helpful”—Milly swung and missed—“don’t say anything at all!”

“There’s no fun in that!”

The broombranch led Milly in a haphazard dance around the tree. They danced over roots and around patches of dirt and over clumps of vegetables and—

“What are you doing?!” came a woman’s voice.

The broombranch abruptly stopped.

Milly saw her chance and grabbed on with both hands.

“LET GO OF THAT BROOMBRANCH!”

But Milly did not let go. She held on even harder as the branch lifted her off the ground and took her in a half-circle round the tree. As she spun around, she saw a woman covered in green running toward her with an outstretched wand. So a witch did live here—just not the one that had taken Cilla.

/>

“It’s a witch!” Jasper said.

“Grab on!” Milly shouted.

Jasper wiggled his butt and jumped toward her as she flew by. He landed on her back and clawed his way up to her shoulder, pricking her every inch of the way.

“Ow! Ow! Careful!”

They climbed higher and higher as the witch flailed her arms beneath them and the broombranch picked up speed. From up here, Milly realized she’d been chasing the branch around an entire garden all this time. All the rows of un-grown seeds had been trampled. By her.

The witch grabbed at her headscarf with both hands, too distraught to know what to do. “My cabbages! My daisies! My home!” She raised a pointed finger. “I don’t know who you are, but I want you to come down here and clean up this mess!”

The broombranch became more and more frantic as it climbed higher in the sky until it suddenly shot off in a random direction, trying to fling Milly and Jasper off.

Milly held on for dear life as they sped over the treetops, her knuckles white with fear.

“Where are we going?!” Jasper said.

“I don’t know!”

On and on they flew, bucking to and fro as the broombranch grew increasingly manic.

“Let go of that broombranch!”

Milly looked back between her arms and saw the witch following them on her own broombranch.

“It’s only a child!” the witch said.

Milly’s arms were growing tired too, and she gasped as her lungs burned with the air whipping by. “Please,” she said. “Please let us down!”

A very agitated voice entered her mind: “Only when you let go!”

Milly nearly let go from the shock of it all. “You talk!”

“Of course I do!”

“Why didn’t you say anything?”

“I did! It’s not my fault you don’t speak tree!”

“Sorry!” Milly said, palms sweaty. “Please let us down, and I promise I won’t try to ride you anymore!”

“Yes! Yes, please!” Jasper shouted. “I’m not sure how well this body would sustain such a long fall!”

“Fine by me!”

“Fine!” Milly said.

“Fine!” Jasper repeated. “We all agree. Just stop already!”

“Let go of that branch!” the witch shouted.

The broombranch divebombed into a tangle of trees until it was wobbling just above the ground.

“GET. OFF.”

The broombranch came to an abrupt halt. The momentum sent Milly and Jasper tumbling onto the ground. When they had stopped long enough to get a sense of their bearings, Milly looked up and saw that they were almost at the very edge of the woods—somewhere opposite West Ernost.

The broombranch shook itself like a wet dog. “Stupid human,” it said, then shot up and toward the witch, who was still headed in their direction.

“Um, Jasper?”

“Run!” the cat said, already on his feet and sprinting toward the edge of the tree line.

Milly’s entire body felt shaken, but she got up anyway and sprinted after the cat.

“Wait! Stop!”

Milly glanced back to see the witch dismounting ungracefully from her broom. She tripped onto the ground, and her head covering fell back to reveal shockingly green hair. She leaned against one of the bending trees, trying to compose herself. “You can’t leave this forest!”

Oh, yes I can! Without a second glance, Milly spun on her heel and tore into the woods.

Milly didn’t have to run long before she saw a bright opening in the trees. After all that had happened in the past two days, her legs were burning something fierce. She didn’t know how much longer she could keep running from everything.

“Don’t leave the woods!” the witch cried. “It’s not safe for you there!”

Milly gritted her teeth and tried to run faster.

“Stop!” The witch sounded farther away, her voice tired. She started to mutter unfamiliar words but stopped abruptly.

Milly looked back and saw the witch standing in place, heaving, one hand holding her side, the other hanging by hip. Shadowy hands and feet stood between Milly and the witch.

Was this the edge of the witch’s domain?

She locked eyes with Milly, then turned toward the shadows.

With a breathless scream, Milly put on an extra burst of speed and broke out from the woods. Near-white sunlight blinded her momentarily. She slowed to a stop and shaded her eyes with a hand. After blinking several times, she realized that the brightness came from a nearby creek. The sun bounced around on the water in broken pieces.

Milly slowed to a walk and giggled—she couldn’t help it. She was just so relieved to be back on the ground. She took her shoes off. Holding them in one hand, she jumped in the water, splashing the cat.

“No! Stop that!”

Milly ignored him and closed her eyes. She waded further and stuck a hand in. The ice-cold currents swam between her fingers and toes, soothing her sore muscles. Frothy bubbles popped like laughter.

When she opened her eyes, she found the cat sniffing angrily at the water on the other side. His fur glistened with a couple drops of water and the ground around him was dotted with tiny damp patches.

“How can you possibly enjoy that?” He glared at his own reflection.

“How can you not?” she responded. She waded out of the water toward the side he was on and collapsed into the grass. She stretched every one of her limbs. She never wanted to fly again. Or run, for that matter.

Jasper let out a long exhale. “Well, I suppose, all things considered, that didn’t go as badly as it could have.”

“Go ahead. Tell me you told me so.”

“Told you so.”

Milly sighed and kept her eyes close. “I don’t even care. I’m just glad we’re out of that forest.” Then she opened her eyes and looked around. “Where are we, anyway?”

The cat took a whiff of the air, then pointed his tail in a direction parallel to the river. “I think I smell something over thataway. The smell is very close, but it’s not particularly strong. Stay here for a minute.”

Without waiting for a response, the cat disappeared into a nearby thicket.

“Jasper,” Milly whispered. “What’s going on?”

She saw a bush rustle and then heard his voice soon after. “Over here!”

Milly ran through the thicket, yearning but nervous to know what the cat had found. She found him dragging a soggy Witch’s Guide out of the river. The book had half its pages ripped out.

“Where are they?” she asked, breathless.

“It’s just the book.” He spat a couple times and stuck his tongue out. “Ugh, gross.”

“Can you smell them?”

He shook his head.

Milly grabbed fistfuls of whatever pages were still intact. “We failed!” She ripped out the wet pages and flung them into the river, one clump at a time. “All of that was for nothing!”

“Milly . . .”

“I’m so useless!” she said. “I was supposed to protect her! I was supposed to be her big sister. But I’m the reason she’s gone. The witch came for me.”

“Milly.” The cat bumped his head against her shoulder. “Look up.”

“Leave me alone.”

“Stop moping for a minute and just look, will you?”

Still holding the torn pages in her hands, Milly sniffed and lifted her head. Her mouth fell open.

“Nignip,” she whispered.

Down the river stood the great city-state. Long, stretched-out walls rose from the ground, made of many chopped trees lashed together. Round holes had been cut into their sides, and the walls themselves were dressed in banners and flags of all shapes and colors. Behind them, Milly saw the faint heads of houses peeking out, stacked upo

n each other in mismatching colors. And of course, rising above all that proudly stood a tall, crooked tower with a half dome for a hat.

There was no doubt about it. That was Nignip, home to all sorts of creatures and music and magicks and foods.

“Come on.” Jasper’s tail brushed against Milly’s shin. “Maybe we can find answers there.”

Milly gulped and turned back for a moment. She searched past the river and beyond the congested forest they had just escaped. She searched for the familiar hilltops that she knew must still be behind it all. Somewhere, St. George’s was waiting for her, and Doris and Nishi and Ikki and all the other girls.

But not Cilla.

Milly let the pages fall out of her hands—faded images of a forbidden text she knew she shouldn’t be familiar with—and put her shoes on. She wiped her nose and threw the book back into the river. She didn’t need it.

CHAPTER NINE

a good witch always follows her nose

Once they passed the outer walls, the collective voices of the city’s inhabitants flooded Milly like a boisterous wave. The deeper she got, the louder they grew. Milly soon realized that the residents there must have been from the southern countries because none of their clothes looked like anything she’d seen before. Some had metal scales pinned to their chests. Others wore colorful hair made of plucked feathers.

Everywhere she looked she saw people like she’d never seen before. Living in West Ernost felt like sitting on a boring blade of grass next to a busy anthill; Nignip was the anthill. Except instead of holes in the ground, it had a wild mishmash of wayward streets. And instead of a queen in the middle, it had its very own residing wizard as self-proclaimed protector.*

She ducked beneath the arm of a sleeveless giant. The giant’s skin was dark gray and her muscles rippled like liquid boulders. In the giant’s raised arm, she held an empty fishing boat.

“Move!” Jasper grabbed Milly’s sleeve with his mouth and pulled her to the side as a troop of long-bearded gnomes scuttled by. Their square spectacles sat atop their blockish noses, which stuck out from their boxlike heads. Even their robes were covered in golden lines and rectangles. Despite the fact that the tallest of them barely came up to Milly’s shoulder, they all looked very important, and none of them looked anyone in the eye.

The Hungry Ghosts

The Hungry Ghosts