- Home

- Miguel Flores

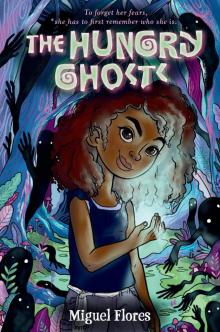

The Hungry Ghosts Page 3

The Hungry Ghosts Read online

Page 3

“Teeth soup,” Ikki added.

“Finger sandwiches!” Marikit exclaimed a little too loudly.

“That’s not true,” Cilla said. She had Junebug pinched beneath one arm while attempting to balance her boxed offering. “Witches aren’t canned knee bulls.”

“What?” Nishi made a face.

“Canned. Knee. Bulls.” Cilla repeated, emphasizing each word as she avoided the cracks in the worn path.

“You mean cannibals?” Milly asked, trying to be helpful.

“That’s what I said.”

“No, it’s not.” Nishi nudged Cilla forward. “Come on, you’re so slow.”

“I heard,” Marikit said, “that they’re the reason the ghosts can’t pass on to the next life.”

Ikki rolled her eyes. “Who told you that?”

“Old Man Tem-Tem. He says that’s what all the shadows are.”

“Well, duh.” Nishi snorted. “That’s why we had to get rid of them all.”

“The shadows?” Cilla asked.

“No. The witches!”

Cilla squinted. “Are all the witches really gone?”

“Don’t you know anything?” Ikki kicked a stray stone down the hill. “They made their last stand in East Ernost. And that’s gone now. So what does that mean?”

“I don’t know . . .”

“There aren’t any more witches anywhere.”

“Wizards got rid of the witches because they stole children,” Marikit said. “And now the ghosts are all that’s left of the children’s souls.”*

Ikki nodded her head vigorously.

Cilla frowned. “I’m sure some witches are nice.”

“Why d’you think that? Have you ever met one?” Marikit asked, eyes wide.

Nishi sneered. “Have you ever met one?”

“That’s not the point!”

“Point is,” Nishi said, “witches are scary and you should be scared of them.”

“All witches have big noses to sniff out their prey,” Ikki tried to helpfully contribute.

“And wrinkled hands.”

“And smelly feet!”

Milly plucked a long blade of grass, then slowed down until she was walking next to Nishi.

“Why do you care about witches so much, anyway?” Nishi got closer to Cilla and lowered her voice. “You should be happy they’re gone. If they were here, they’d probably catch you in a great big net. Then they’d bring you to their home and sing a wicked song while boiling water to cook you up in a—”

Milly tickled Nishi’s elbow with the blade of grass.

Nishi screamed, almost dropping her box in the process.

Doris spun around, eyes ablaze. “Shhhh. Show some respect!”

All the girls hushed. Nishi glared at Milly and stuck out her tongue before finding a new place in the line.

Milly tossed the blade away and winked at Cilla. “Don’t listen to her. No one’s seen a witch in years, anyway.”

But Cilla didn’t respond like Milly had hoped she would. Instead, she looked down at her feet and kept walking.

Nishi looked like she wanted to say something else in retort, but Milly glared her back into silence. Instead, Nishi just exhaled through her flared nostrils.

Seeing an old couple ahead of them, the girls quieted and didn’t say another word on their journey along the winding path.

* * *

The Hallow was a half-circle of stones that surrounded a large white tree growing out from the very edge of the cliff. Old Man Tem-Tem said that the tree had been consumed in a fire and lost its entire crown of leaves. Instead of dying, the tree was blessed (or cursed, depending how you thought of it) to grow for eternity. Even though it appeared completely dead on the outside.

Some nights, the villagers swore they could see little balls of fire still dancing in its branches. They claimed these dancing lights were the departed ghosts, and that if one were ever lost, all they had to do was follow these lights back to the tree in the Hallow.

They called the tree Elma.

When Doris and the girls arrived at the Hallow, they saw some of the villagers already laying down their offerings on the stones and whispering prayers for whoever it was they remembered or missed or wished would come back one day to visit.

Some of the girls had prayers already prepared, mostly for old parents to come back or for new ones to take them away. Others stared into their boxes with gurgling stomachs, wondering when they’d be allowed to get back to St. George’s and eat.

As for Milly, prayers felt too much like dreams. She didn’t really have any for herself. She knelt for a short while and placed her box down next to Ikki’s. She had given up on asking for parents a while ago. She was almost thirteen, after all. Practically her own person.

She did, however, still keep a list of prayers for the others. Things like:

Please fix Doris’s brain.

Please make Nishi shut up sometimes.

Please give Marikit a friend.

While she muttered her short, scattered prayers, she looked over at the others—some intensely staring at their boxes, others yawning into their fists. Cilla was mumbling something to Junebug.

Suddenly, a small shadowed hand reached toward Cilla’s head from the nearby tree. Milly jumped up.

“Cilla!” she said.

The hand quickly pulled back.

Cilla stared at Milly, a very confused expression on her face. There was no sign of shadows around her.

Milly shook her head and sat back down. A cold wind blew across the sweat on Milly’s brow as some of the others glanced at her, but she didn’t look up. The wind brought with it the scent of something . . . burnt. An odd thought crossed her mind. She wished she could ignore it, but the idea was too strange. Too specific.

She closed her eyes and muttered one last request.

“Please don’t let Cilla be a witch.”

CHAPTER FOUR

the girl who talks to vegetables

In the early dark, Milly sat in the library. The library was a circle of shelves and bookcases with very few actual books or scrolls to decorate them. At its center was the giant, winding bookshelf she climbed to get to the attic. Distinct footprints punctuated the dust that covered it from bottom to top.

On the side where she was sitting was a wall of large side-sliding windows that stretched down to the floor.

Whenever Milly needed to breathe or sit or hide or ponder, she always returned to the library. Usually, she’d climb up the bookshelf and find her place by the half-window, curl up with a blanket, and read by sundew or moonglow. She would stay in the stories for as long as she could, chewing up the words and mulling over the inky depictions of faraway lands that slipped between her teeth and tongue.

But today, the words that so often provided refuge felt suffocating.

Instead, she pulled open a wall-window and sat with her arms wrapped around her stomach, facing the breadth of ocean that lay past the sea of fog. She let her feet hang in the thick fog surrounding the house. The winds were especially ferocious today, almost blowing through her, pulling her hair back and daring her to jump.

The waves in the distance formed crests, momentary mountain peaks that rose for one second and crashed down the very next. It was their impermanence that made them so fascinating. That made them almost alive.

Milly had avoided Doris and the other girls since dinner the previous day and was taking time to be alone before she had to get back for breakfast. This was the kind of space she needed. Big space. Air too unruly to be bound by walls. Waves too wild to hold shape.

She didn’t know why, but she wanted to feel small.

She closed her eyes and breathed in the salty air.

But, too soon, the world decided that she needed a rude interruption.*

Milly

blinked her eyes open. She thought she’d heard noise from outside the house. She stood and poked her head out into the chilly air.

The most dangerous part of living on the side of a cliff wasn’t the storm, but what came after: a large, rolling wave of white fog that came in from the seas and blanketed the ground all around St. George’s. It swallowed up the green fields and hid the cliff’s edges from sight, making it all too easy to tumble down. No one was allowed outside this soon after a storm, especially not on this side of the house.

Milly began to sit back down. Maybe she’d just imagined the sound.

A girl’s voice drifted from around the corner of the house. If one of the girls was lost in the fog, they might need her help to get back inside.

Milly dry-swallowed and looked down. She knew the ground was just a short drop from St. George’s, hidden somewhere beneath the fog. But even knowing that, the ground seemed farther away when invisible.

She scrunched up her face.

Breathe.

Milly jumped down and landed on all fours with a jarring thump. She pressed her hands against wet grass and dug in her fingers. The blades tickled, poking out between her toes and against her shins like cold kisses from the earth.

She rubbed the dirt off her hands, then reached out to feel the familiar textured walls of St. George’s. Slowly, she stood, until the fog came up to her hips. There was nothing but the house’s wooden beams and the occasional sounds of a muddled voice to guide her forward.

Step by step, she made her way around the back of the house to the squash garden. She imagined how it might usually look. Vines roped beneath and over one another. Pinched leaves sticking out from the places she hadn’t stomped over during harvest. Wild and always messy.

Instead, when she turned the corner, she saw nothing but a continuous wall of white. It was so thick she could bite it.

“Nasty fog, I wish you’d let me see something.”

As if in response, a soft wind blew through and thinned the fog just the tiniest bit. Faint flecks of green revealed themselves before her. With renewed confidence, she let her fingertips leave the house behind and took larger, bolder steps until she saw the nearest corner of the garden.

And, next to the garden, Cilla, who was squatting. And talking to the plants.

Milly let out a huge sigh. That girl could talk the ears off anything, even things that didn’t have ears.

“What are you doing out here?” Milly asked.

Cilla spun toward Milly, and a wide smile illuminated her face. “Oh, good! You can help us! We’re trying to learn a new trick.” She turned back around and muttered something.

“A trick?” Milly looked over Cilla’s shoulder and saw a drawing of a squash. It looked familiar somehow. “Cilla, what are you reading?”

“We don’t know. We didn’t recognize it from your other books. It has cool drawings though! They looked like directions for growing plants.”

Milly’s took another step, and her chest tightened.

It was a page from the Witch’s Guide.

“Cilla,” Milly whispered. “Where did you get that?”

Cilla looked up at her, obviously confused. “It was in the attic with your other books.” She looked down, then up again. “Is it yours?”

“No! I mean, yes. I mean—well, you can’t use that one. Here,” Milly said and reached out a hand. “Give it to me.”

“Why?” Cilla grabbed the book and clutched it to her chest with Junebug. “I can read things, too! You didn’t steal it, did you?”

“Of course not. I just need you to give it to me right now.”

“No.”

“Cilla—”

“No!” Cilla looked at the book’s cover. “Everyone keeps saying magicks are bad, but this book isn’t bad. It’s helpful! It has directions for lots of useful things. Like gardening. And cooking! And, and—”

“Please. You’re gonna get us in trouble!” Milly’s whispers started to sound less like whispers.

Cilla dropped her gaze and wouldn’t look at Milly, her eyes wet.

“Cilla.” Milly softened her voice and put her hand on Cilla’s shoulder. “Come on, let’s go home and you can put that book back where you found it.”

The girl kept her mouth shut and shook her head from side to side.

“Cilla.” Milly said Cilla’s name with a tone of danger. It was a voice she never practiced and rarely used. In fact, she could count on one hand how many times she had used that voice, and all but one of those times had been with Nishi. “You know you shouldn’t be out here. Let alone reading about witches. Who knows who, or what, is out here listening.”

Cilla opened her mouth to object, but Milly continued.

“You either give me back that book or I’m dragging you back to St. George’s and telling Doris that you were out here in the fog.”

Cilla’s eyes widened. “You won’t.”

Milly lowered her voice. “I will.”

Cilla’s lower lip quivered and she looked out into the garden, her eyes darting back and forth. Then she ducked her head and whined, “I can’t.”

Milly’s mouth fell open, but no words came to mind. Cilla could be stubborn, but never this stubborn. Milly put both hands on the younger girl’s shoulders. “Cilla, look at me. I know you think this isn’t a big deal, but it is.”

“You don’t trust me. You never do.”

“I want to, but you have to trust me, too.”

Tears formed in the corners of Cilla’s eyes.

Milly exhaled, convinced the tears were an act. Cilla’s theatrics wouldn’t win her over this time. She grabbed Cilla’s arm. “Come on. We’re going back to the house.”

“No!”

“Ci—”

“NO.” Cilla twisted out of Milly’s hand and tore into the fog.

“Cilla! Oh, what have I done? Come back!”

Milly tore after the girl. Her feet thudded against the damp clumps of grass and dirt. She searched for even a blue puff of Junebug. She saw nothing.

“Milly.”

“Cilla?!” she shouted. “Where are you?”

“Milly,” the voice said again. It came as a cutting whisper, as if from the wind itself.

Milly slowed to a walk, panting for breath. “Who—gasp—who is that?”

“Milly.” The voice came from ahead, distant and beckoning. It had gotten softer.

“Wait,” Milly said, picking up her pace. “Come back this way!”

Something struck her shin. She tripped and put her hands out in front of her but found nothing to catch her fall. She tumbled somersaults down a steep incline, the air in her lungs escaping her like exploding bubbles, until she found the bottom of the slope.

Disoriented, she grabbed at tufts of grass and propped herself up. She was in a shallow pool, where the fog only came up to her wrists. Ahead of her she saw Cilla clutching the book in her arms. The wind whipped the hair around Cilla’s cheeks and Milly heard the crashing waves somewhere nearby.

“Cilla!” she called, her voice hoarse and tiny. Getting to her feet, she stumbled forward once more. “Cilla, come back toward me!”

Cilla shook her head and took one step back. “We don’t want to.”

“Cilla, please. You have to trust me!”

Cilla shuffled her other foot backward.

Milly gulped and reached out her hand. “Cilla, if you’re not careful you’ll—”

Cilla’s mouth dropped open in surprise.

Right before she fell off the cliff.

AN INTRODUCTION TO CHAPTER FIVE

the little winds

When the prayers became quiet, so did the magicks. Not because Arrett wanted to punish anyone, but because Arrett knew that no person’s heart could have magicks if it were also full of too much want.

The South Wi

nd didn’t understand. He demanded that Arrett give up their magicks once more, without the prayers. Arrett tried to explain the importance of trading prayer for magicks, how delicate the mathematical equation was that lay in every selfish heart, but the South Wind wouldn’t hear of it. And so, Arrett had no choice but to consult Ovid, the smallest of the giants. Arrett asked Ovid to chain down the unruly wind.

Unfortunately, when the South Wind was involuntarily forced to retire, he left the world of Arrett in quite an awkward state. Suddenly, the seasons were skipping entire days and the calendar missed all of its important holidays. Snow tripped into summer, and the other winds forgot which direction hurricanes spun in.

In other words, the South Wind left some pretty big shoes to fill. Like, a size seventeen at least. These little winds, these young little upstarts, I don’t think any of them could have been any bigger than a size three. Maybe four. And that’s a very generous estimate!

Arrett needed to find a new South Wind. And fast. The immense pressure required all of the winds to stop doing their jobs and search. Almost all of them.

The exception I’m talking about is a little wind so young and so small he doesn’t even have a name yet. After the war ended, the little wind never got the memo about searching for a new wind, and spent his time scurrying around the bottom of the cliff of West Ernost, doing his very best to catch the prayers of the locals and carry them to who knows where. Honestly, he’s not very big and his arms are rather skinny, so most of the prayers fell through.

But one day, a little girl threw in a prayer so small it wouldn’t have been noticed by anyone with bigger arms. Despite its size, the prayer she threw was so heavy that the moment this wind caught it, he didn’t have the strength to carry any of the others he had collected. And before he had even made it away from the cliffside, another little girl tossed herself from the cliff and landed on his head!

She landed so hard that, quite by accident, the prayer passed into him. It’s not generally a little wind’s job to take on these prayers—only to carry them back to the heart in exchange for a little bit of magicks—but this wind had something to prove.

The Hungry Ghosts

The Hungry Ghosts